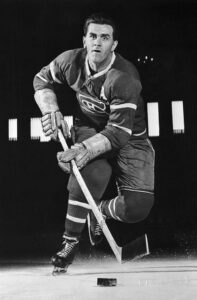

In the long and storied history of the Montreal Canadiens, there has been one player that can be looked back on as having the biggest impact, not only on the ice but also in terms of impact on the franchise and culturally as well. The player is Maurice “the Rocket” Richard.

The Canadiens were no strangers to star players wearing their uniform. From the NHL’s original scoring star, Joe Malone, to the iconic superstar Howie Morenz, whose early death led to the first “state” funeral of a hockey player. He was laid in state at the Montreal Forum where tens of thousands of fans filed through to pay their respects. Yet none of them, or any player since, has had the impact Richard had on the team and the fan base. He set a high bar for every generation to follow, overcoming many forms of adversity such as injuries and even cultural bigotry to become the greatest hockey player of his generation and one of the greatest in NHL history.

No player has cast a more imposing shadow over his city, province and culture than Maurice “Rocket” Richard. Born and raised in Montreal he became the unquestioned idol for all Francophones living in the province of Quebec.

Savior of The Franchise

In the 1929-30 season, the NHL was thriving. It was comprised of 10 teams set up in two five-team divisions. The Canadiens started the decade off strong, winning back-to-back Stanley Cups in 1930 and 1931. However, the 1930s saw the Great Depression hit the North American economy hard. Fortunes were lost, families lost their homes, and all their possessions, and many were left as nomads looking for any job they could find.

This financial reality took its toll on the NHL, which came close to folding as a league entirely. Over this decade of darkness, the league had to contract as teams such as the Philadelphia Quakers, Ottawa Senators (moved and became the St-Louis Eagles), and Montreal Maroons all folded. Over this time, the New York Americans were owned by the NHL from 1936 until their folding in 1942. The Canadiens limped through the decade in the standings and ticket sales.

At the onset of World War Two (WW2) in the 1939-40 season, the Canadiens finished last in the NHL, winning only 10 games. That edition of the team had a woeful .260 winning percentage, which remains as the worst in the franchise’s 114-plus year history. Partially due to the team’s poor play, the Canadiens only drew an average of 3,000 fans per game, leading then-owner J.S. Earnest Savard and his partners to consider suspending operations (as the Maroons had) at least for the duration of WW2. Instead, they sold the franchise to the team’s landlord, and owner of the Montreal Forum, the Canadian Arena Company.

It wasn’t until the 1943-44 season that the Canadiens had found the ingredient that would make them a contending team, but also draw fans to the Forum in droves, the season Maurice Richard arrived and found his role. As a rookie in 1942-43, he played only 16 games, then suffered a season-ending injury. With the final year of his contract remaining, Richard had to prove himself worthy for head coach Dick Irving to give him playing time. Once he did, and Irving had put Richard on a line with Toe Blake and Elmer Lach, the Canadiens became unstoppable. This line became one of the first famous lines, nicknamed the “Punch line”. They dominated the NHL for four seasons, winning two Stanley Cups in that time.

A Scoring Legend is Born

Led by the Punch Line Montreal in 1944–45, the team won 38 games (out of 50), losing only eight, and Richard was the focus of the media and fans as he chased the NHL’s single-season scoring record of 44 goals (set during WW1), held by Joe Malone. That season saw Richard set the record for most points in a single game: eight. He racked up five goals and three assists in a 9-1 victory over the Detroit Red Wings on Dec. 28, 1944. Legend has it that he had spent the entire day moving his family into their new home that day. Since Richard’s eight-point night only 15 other players in NHL history have repeated that feat. Only one, Toronto Maple Leafs legend, Darryl Sittler scored more. His 10 points in a game over the Boston Bruins on Feb. 7, 1976, is the only time anyone beat Richard’s single-game scoring feat.

That same season, Richard attempted to do something no one had ever done, to be the first player in league history to score 50 goals in a 50-game season. This was at a time when the NHL had a 50-game schedule, meaning it was an attempt to be the first to average one goal per game, a feat repeated only four more times in NHL history.

In 1944-45, Richard did break Joe Malone’s goal-scoring record when he scored his 45th goal. After this, no team wanted to be the one that allowed Richard to set a benchmark for goal-scoring greatness. They did almost anything to prevent him from reaching the 50-goal mark. He was slashed, elbowed and held as no team wanted to be known as the one that gave up the milestone goal. It didn’t matter as Richard scored his 50th goal in Boston on goaltender Harvey Bennett (who never played an NHL game again) at 17:45 of the third period in Montreal’s final game of the season. This record, previously considered impossible to achieve, lifted Richard to the status of provincial hero in Quebec.

Scoring 50-in-50 embodies many things. It demonstrates a player’s scoring consistency. Their determination to overcome their opponents’ best efforts. Their ability to score at important moments. Most of all, it is an achievement that places those who succeed in doing so in elite company. Scoring a goal in the NHL is one of the most important, yet the most difficult skill set in the sport. There is a saying, “You can’t teach scoring”. Scoring is hard work, needing to process the defensive schemes in front of you, anticipate your team’s offensive positioning, read and react to an ever-changing situation then determine correctly within a split second where to shoot to score the goal. The best goal scorers in the game today will miss around 90% of their shots taken. This is in part why “snipers” are exciting to watch and needed for so many teams to have success.

Richard’s achievement has been the bar set for a goal scorer to be considered elite in a single season. The 50-in-50 isn’t done over just any 50-game stretch by a player through a season. To be officially recognized for the 50 goals in 50 games can only be seen as an official achievement if a player completes it within their team’s first 50 games, reflecting Richard’s achievement in a 50-game season. There have been many great goal-scorers in the history of the NHL. Many of them are legends in their own right, winning championships, scoring titles and even being inducted into the Hall of Fame. Out of all of them, only an elite few have been able to complete this grand scoring achievement

Since Richard, only four other players in NHL history, Mike Bossy, Wayne Gretzky, Mario Lemieux and Brett Hull have been able to duplicate his heroics. This highlights just how difficult this achievement is to attain as only the greatest goal scorers in NHL history have been able to achieve it. Even Alexander Ovechkin, who is the chase for Gretzky’s career goals record has never been able to do so. The rarity of this accomplishment is why it captivates fans of this game, and why the trophy for top goal scorer each season is named after Maurice Richard.

Riots and Revolutions

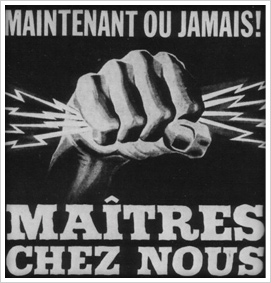

Scoring 50-in-50 made Richard an icon, a symbol for French-speaking Quebecois of their ability to achieve greatness. He was also seen as the premier star in the NHL at that time by the fans in Montreal who saw him as an extension of themselves at a time when French-speaking Québécois were seen as an inferior population in their province. French-Canadian nationalism was in its infancy in the 1950s and Richard became a symbol for it.

Richard’s career coincided with a time in Quebec referred to as la Grand Noirceur, (the Great Darkness), characterized by rural Catholic values, insular traditionalism, and conservatism. In that era, despite their majority status, francophones in Quebec had higher levels of poverty and unemployment. The Richard Riot, known as L’Affaire Richard in Quebec, is seen as key in that era ending. What followed was referred to as the Quiet Revolution. That was a period that had brought about intense social change. This included the secularization and urbanization of the province that saw a mostly rural society transform as if overnight. Many of the conservative, religious traditions were replaced by more modern, liberal attitudes.

Late in the 1955 season, Richard and the Canadiens were in Boston as they looked to get the win and try and secure the top seed for the NHL playoffs. During this game, Richard was slashed in the head by Bruin Hal Laycoe. The referee paid little attention to the infraction, letting play continue. Richard, known for his fiery personality, sought revenge and went on the offensive to avenge himself and returned the favour to Laycoe with a stick to the head. During the ensuing altercation, Richard was held back by linesman Cliff Thompson as Laycoe continued to punch Richard. Richard had said that he had warned the linesman to let him go multiple times, but when he hadn’t and Laycoe continued landing blows, Richard punched Thompson so he could defend himself from Laycoe. Coincidentally, Thompson played defence in the Boston Bruins organization from 1939 until 1950 before becoming an NHL official.

Following this on-ice brawl, Boston police attempted to arrest Richard but Montreal’s players and coaches, as well as Bruins officials, swayed that attempt. Two days later, Richard was suspended for the remainder of the season and the playoffs. To Canadiens fans, it was seen as a way to ensure Montreal would not win the Stanley Cup. To many Francophone Quebecois, this decision to suspend Richard by Clarence Campbell represented another example of English Canada’s dominance over French Canada. Views on the suspension were seen differently based on linguistic lines. The French media supported Richard while the English media supported Campbell. The morning after the suspension was announced, the French-language newspaper Montreal-Matin printed an angry cartoon depicting Campbell’s severed head dripping with blood. Campbell also received death threats, and there were threats made to blow up NHL headquarters, then based in Montreal.

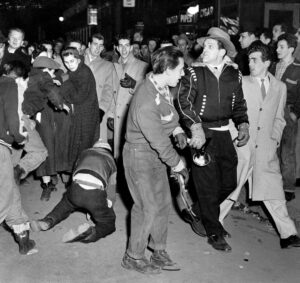

It was the longest suspension that Campbell had ever ruled on at that point and many in Montreal didn’t just think it was too harsh, but that it was inspired by anti-francophone prejudice. When Campbell defied requests by Canadiens management, then Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau, and Montreal’s law enforcement authorities. Arrogantly, he dared to attend the next Canadien game in person, held on St. Patrick’s Day and predictably, things got out of hand. The crowd booed him, threw rotten vegetables in his direction and eventually, someone punched Campbell in the face. The fans in the Forum roared their approval. During the ensuing chaos, tear gas was thrown and the “Richard Riot” began.

This riot went on for hours along Sainte-Catherine’s street. It saw English-owned businesses looted, several fires being set, rioters overturning police cars and assaulting law enforcement. It was reported that there was more than $100,000 in damages done. There were over 70 arrests made and twelve policemen and 25 civilians suffered injuries. As the local populace felt they were dominated and discriminated against by the wealthy minority English-speaking population, the frustrations of the populace were unleashed and led to this riot.

There were fears that another riot would begin the following day and officials pleaded with Richard to make a statement. Eventually, he did provide one in both French and English to a national audience.

“Because I always try so hard to win and had my troubles in Boston, I was suspended. At playoff time it hurts not be in the game with the boys. However, I want to do what is good for the people of Montreal and the team. So that no further harm will be done, I would like to ask everyone to get behind the team and to help the boys win from the New York Rangers and Detroit. I will take my punishment and come back next year to help the club and the younger players to win the Cup.”

It’s generally accepted that the Richard Riot of 1955 was one of the key events that sparked the Quiet Revolution, a complex time that saw the secularization of civil institutions and strengthened provincial control over its economy. The Richard Riot was about more than just hockey, it was the beginning and significant cultural transformation.

Legacy

That benchmark in scoring, 50 goals, was such an impressive feat that it became the benchmark of scoring greatness. it would take another 16 years before the second player ever, Bernie Geoffrion managed to score 50 goals in a single season, and that was after the NHL expanded their season schedule to 64 games. It took 35 years before anyone matched Richard’s feat of 50 goals in 50 games. Coupled with being the first 500-goal scorer in NHL history (the NHL record before this was 324 career goals), the ‘difficulty’ of matching Richard’s early 50 in 50 feat led many to declare the Rocket to be the greatest scorer of all time – with the NHL creating an annual trophy in 1999, the Maurice “Rocket” Richard Trophy, to be presented to the top goal scorer in the league.

Few athletes can say they led their team to multiple championships over two decades. Fewer still can say they were able to save a franchise from extinction. But only one can say all of that and that he captained a team to five consecutive Stanley Cups and had such a cultural impact as to help change an entire society. Because of his impact on the sport and Quebec’s culture, fans of the Montreal Canadiens have never stopped loving him. His legendary ovation in the ceremony for the final game played at the Montreal Forum shows that best. An ovation that moved fans, and Richard to tears. This is a love that went beyond just hockey.